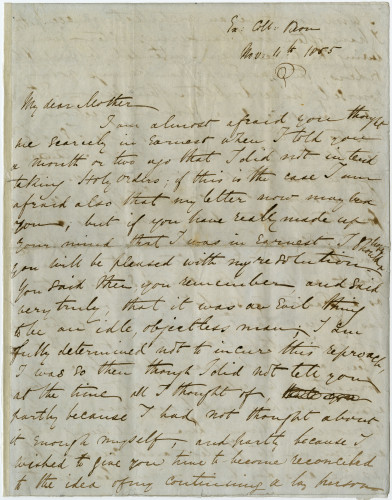

William Morris tells his mother of his decision to forsake Holy Orders for a career in architecture

Ex: Coll: Oxon

Nov: 11th 1855

My Dear Mother

I am almost afraid you thought me scarcely in earnest when I told you a month or two ago that I did not intend taking Holy Orders. If this is the case I am afraid also that this letter now may vex you; but if you have really made up your mind that I was in earnest I should hope you will be pleased with my resolution. You said then, you remember, and said very truly, that it was an evil thing to be an idle objectless man; I am fully determined not to incur this reproach, I was so then, though I did not tell you at the time all I thought of, partly because I had not thought about it enough myself, and partly because I wished to give you time to become reconciled to the idea of me continuing a lay person. I wish now to be an architect, an occupation I have often had hankerings after, even during the time when I intended taking Holy Orders; the sign of which hankerings you yourself have doubtless often seen. I think I can imagine some of your objections, reasonable ones too, to this profession – I hope I shall be able to relieve them. First I suppose you think that you have as it were thrown away money on my kind of apprenticeship for the Ministry; let your mind be easy on this score; for, in the first place, an University education fits a man about as much for being a ship-captain as a Pastor of souls; besides your money has by no means been thrown away, if the love of friends faithful and true, friends first seen and loved here, if this love is something priceless, and not to be bought again anywhere and by any means; if moreover by living here and seeing evil and sin in its foulest and coarsest forms, as one does day by day, I have learned to hate any form of sin, and to wish to fight against it, is not this well too? Think, I pray you, Mother, that all this is for the best; moreover if any fresh burden were to be laid upon you, it would be different, but as I am able to provide myself for my new course of life, the new money to be paid matters nothing. If I were not to follow this occupation I in truth know not what I should follow with any chance of success, or hope of happiness in my work; in this I am pretty confident I shall succeed, and make I hope a decent architect sooner or later; and you know too that in any work that one delights in, even the merest drudgery connected with it is delightful too. I shall be master too of a useful trade; one by which I should hope to earn money, not altogether precariously, if other things fail. I myself have had to overcome many things in making up my mind to this; it will be rather grievous to my pride and selfwill to have to do just as I am told for three long years, but good for it too, I think; rather grievous to my love of idleness and leisure to have to go through all the drudgery of learning a new trade, but for that also good. Perhaps you think that people will laugh at me, and call me purposeless and changeable; I have no doubt they will, but I in my turn will try to shame them, God being my helper, by steadiness and hard work. Will you tell Henrietta that I can quite sympathise with her hard disappointment, that I think I understand it, but I hope it will change to something else before long, if she sees me making myself useful; for that I will by no means give up things I have thought of for the bettering of the world in so far as lies in me.

You see I do not hope to be great at all in anything, but perhaps I may reasonably hope to be happy in my work, and sometimes when I am idle and doing nothing, pleasant visions go past me of the things that may be. You may perhaps think this a long silly letter about a simple matter, but it seems to me to be kindest to tell you what I was thinking of somewhat at length, and to try, if ever so unsuccessfully, to make you understand my feelings a little: moreover I remember speaking somewhat roughly to you when we had conversation last on this matter, speaking indeed far off from my heart because of my awkwardness, and I thought I would try to mend this a little now; have I done so at all?

To come to details on this matter. I purpose asking Mr. Street of Oxford to take me as his pupil: he is a good architect, as things go now, and has a great deal of business, and always goes for an honourable man; I should learn what I want of him if of anybody, but if I fail there (as I may, for I don’t know at all if he would take a pupil) I should apply to some London architect, in which case I should have the advantage of living with you if you continue to live near London, and the sooner the better, I think, for I am already old for this kind of work. Of course I should pay myself the premium and all that.

My best love to yourself, and Henrietta, and Aunt, and all of them:

Your most affectionate son

WILLIAM.

P.S. May I ask you to show this letter to no one else but Henrietta.