Discover object stories written by the 18-25 year olds who took part in the William Morris & Art from the Islamic World curatorial interpretation professional development course in 2024.

The course was led by Shaheen Kasmani — artist, curator and educator.

Participants: Saarah Ahmed, Mara Ahmed, Noor Ahmad, Mohsina Alam, Leyah Dean, Zineb Dinia, Sara Ismail, Iman Javaid, Sana Malik, Hana Mehmed, Sumayyah Mirza, Behdad Monsef, Ebrahim Piperdi, Zahra Quadri, Zara Rawat, Lina Rashad, Ayan Raja, Tayyabah Tahir, Tasmiya Tasmi, Safiyah Yacoobali.

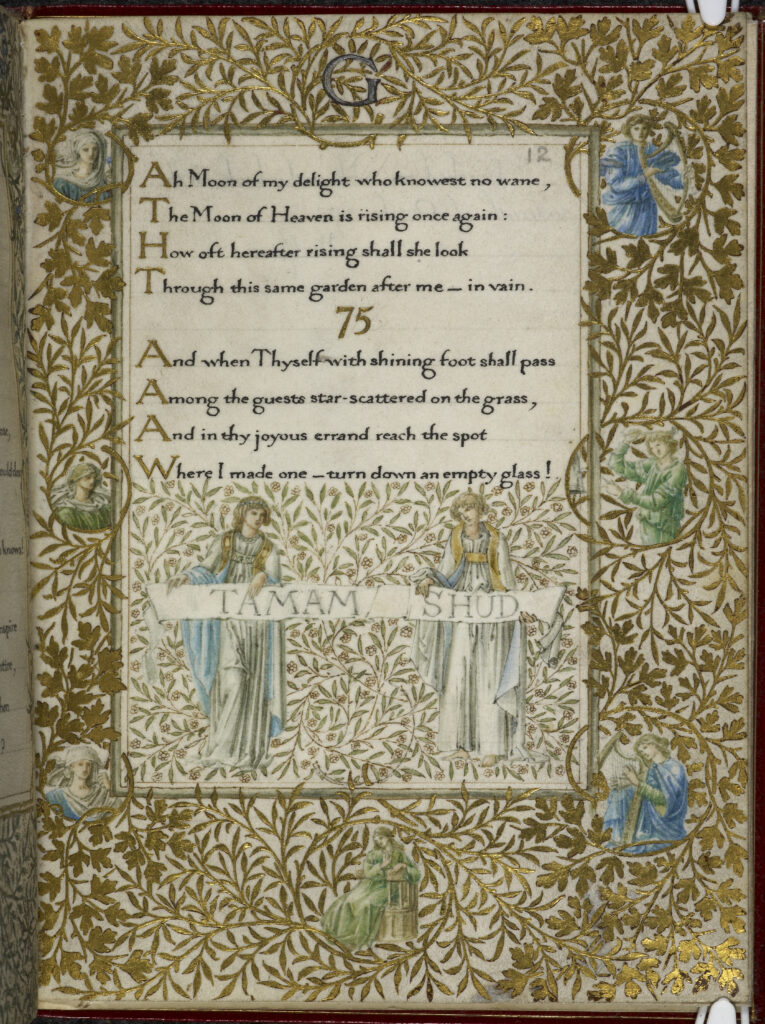

The Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám

By Iman Javaid

In Persian poetry, a rubáiyát refers to a verse consisting of four-line stanzas. The specific title was chosen by Edward FitzGerald in 1859, when he translated what would become one of the most cited works in the English language. The poem was so significant that friends of FitzGerald established The Omar Khayyam Club London in 1893, which still hosts meetings today.

Despite his status as a notable poet amongst Western academics, in the East, Khayyam was renowned for being a student of Ibn Sina (Avicenna). His contributions to geometry and algebra facilitated Khayyam’s astronomical interests and inspired new lines of mathematical thinking, strengthening the Islamic world during their pioneering Golden Age. Perhaps most remarkable was his influential work refining the Jalali calendar, a solar calendar still used in Iran and Afghanistan, as it is more accurate than the Gregorian calendar.

Morris himself was fond of poetry, having gained traction for his poem ‘Earthly Paradise’, which retells myths and legends from Greece and Scandinavia. Morris also planned to create an illuminated version of his poem ‘Love is Enough’ as well as his contemporary novel, yet he was unable to complete these. However, for this piece he turned to Iran, to illuminate the work of Omar Khayyam. Of all the works Morris completed during the five years he dedicated to illumination, this work, which he finished in October 1872, was the most ornate in terms of the gold detailing and dainty yet, natural adornments. As Morris himself wrote: ‘gold is used in this book with a special ingenuity and enjoyment’. He described the feeling of viewing such adornments as akin to the experience of viewing a piece of Syrian weaving of gold and silk.

William Morris, Edward Burne-Jones and Charles Fairfax Murray, spring 1871–16 October 1872

Handwritten in ink, with decoration in watercolour, bodycolour and gold

British Library

Image: From the British Library Archive/Bridgman Images

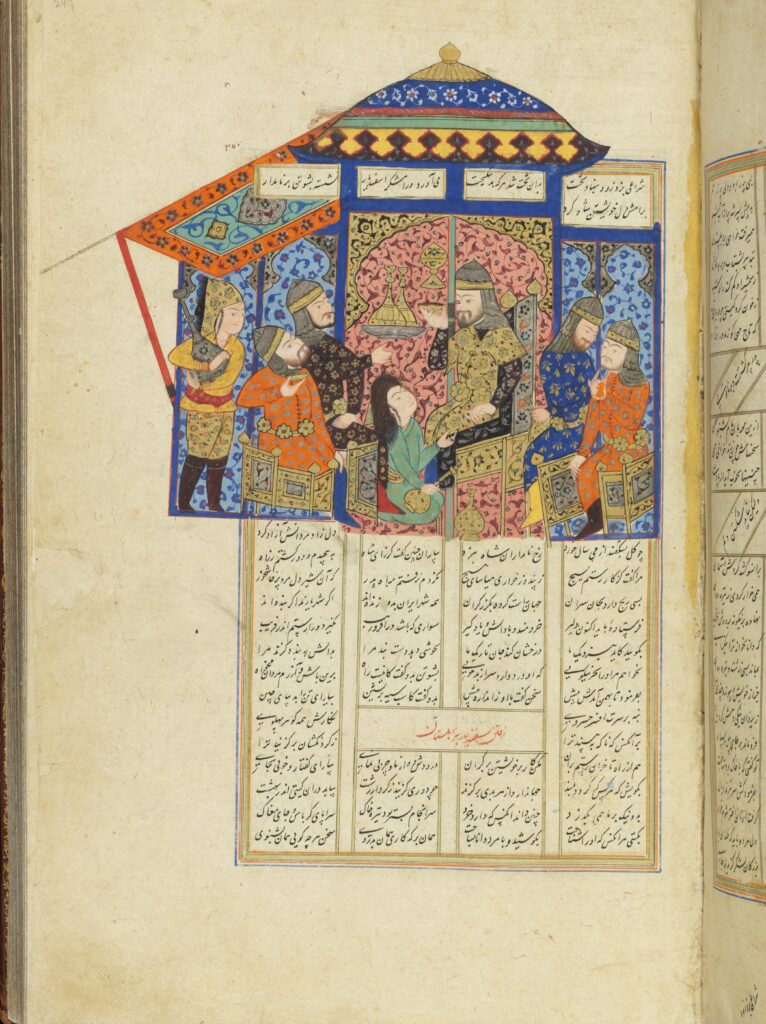

Shahnameh

By Zara Rawat and Sana Malik

The Shahnameh is an illuminated manuscript containing a Persian epic written by the poet Ferdowsi over the course of three decades, it was supposedly completed in 1010. The epic was commissioned by Sultan Mahmoud of Ghazni, as a symbol of his political status as well as a way to preserve the Persian language and culture.

The story depicts a series of kings’ journeys, myths, and legends, serving as a document of history. The tales are drawn from cultural exchanges, religious texts, and Persian heroes. The rich oral tradition that was woven into the fabric of society is bound into a written and illustrative workthat has captivated many.

This illuminated page is richly decorated in floral motifs known as Khatai, that entirely cover the architecture, vessels and garments of the characters depicted. It illustrates drinks shared between companions under a canopy, contrasted with bright colours and framed by the iconic nasta’liq script.

In the 1870s–80s this edition was acquired by William Morris, who also produced his own literary texts, including an epic and a partial translation of Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh. Much like the significance of the oral tradition, the written, tangible document would inform and inspire the intellect. Morris looked to such works of literature and design to engage and stimulate the mind.

Morris’s unceasing fascination with ‘Persia’ led him to consciously mislabel arts from various regions, such as Ottoman Turkey, under this umbrella term despite his ability to identify local artistic styles. Though he travelled no further east than Italy, his extensive collection and artistic renditions reflect the profound inspiration he drew from the ‘Islamic’ world.

Unrecorded maker, Northern Iran, perhaps Astarabad (Safavid), 1620–21

Illuminated manuscript

The Syndics of the Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge

Image: © The Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge

Woman’s Jacket

By Ebrahim Piperdi

This jacket from the Qajar period (1794–1925) is an incredible example of 18th-century Iranian textile craftsmanship. The garment combines Iranian silk and metal thread, lined with European roller-printed cotton, designed with aesthetic appeal and practical functionality. The jacket was typically worn over a blouse and featured a wide bottom section, allowing for a full skirt to be worn.

Iranian textiles, known for their colour, delicacy, and beauty, faced high taxation compared to European goods. The design of the jacket, which features small clumps of flowers on a blue indigo background, is similar to the geometrical patterns and floral motifs seen in Islamic art which inspired the textile designs of William Morris, especially his textile Flowerpot, designed in 1883.

Due to the shifting of power in this period, the Qajar family constantly strove to establish their historic right to rule. Fath-Ali Shah Qajar (1769–1834) was ruler of Iran from 1797-1834. During his reign his public image was heavily curated, crafted, and purposefully designed to display opulence. He meticulously used art as propaganda, adorning his many palaces with portraits depicting himself in the same pose and similar style of garments, jewels and swords throughout his dynasty. He frequently referred to Nadir Shah (1688-1747), the most successful ruler of Iran during the 18th century, by having himself painted almost identically.

Unfortunately, no information could be found on how the jacket was obtained by Morris. This highlights the imperial and corrupt attitudes of the British towards artefacts from the Middle East. Major art institutions often value possession over proper documentation or preservation. Glossing over the history of the possession of artefacts is not beneficial for audiences, as it is vital to our understanding of the exoticism Middle Eastern and Asian people faced. This oversight amplifies the need for more transparent and ethical practices in the acquisition and preservation of heritage.

Unrecorded maker, Iran (Qajar), 1800–60

Silk brocade, with a satin base, lined with printed cotton

Birmingham Museums Trust

Design for Medway

By Mohsina Alam

Medway was created using natural dyes and an indigo discharge technique, influenced by the naturally dyed Indian textiles that Morris and his contemporaries admired. Although using natural indigo resulted in richer colouring, the process of cultivating and importing indigo to Europe was exploitative. Many farmers were subject to unsafe working conditions with almost no pay.

This indigo colouring is reminiscent of the blues that prevailed in Persian and Ottoman designs. The dominant flower in Medway is the red tulip, which closely aligns with ideas of the ‘Islamic Garden’. Iznik craftsmen were inspired by the rich red colour of a wild tulip named the tulipa sprengai, which later became iconic in Iznik ceramics. Morris himself possessed Iznik plates which featured the same red tulips.

The stems and flowers depicted in this design are biomorphic in nature. Morris avoided realistic depictions of living things in his work, choosing to abstract animals and plants and show them in movement to reflect the depth of nature. This is similar to the intentions of Islamic artists, who adopt biomorphic stylisation, as they too wanted to capture the essence of nature. Many believed that the realistic depiction of life forms should be left only to God.

The references to Islamic art in Medway remind us that Morris’s work should be situated within a long history of creation that would not exist without cultural exchange, and in some cases, exploitation.

William Morris, designed 1885

Watercolour, pencil and ink on paper

William Morris Gallery

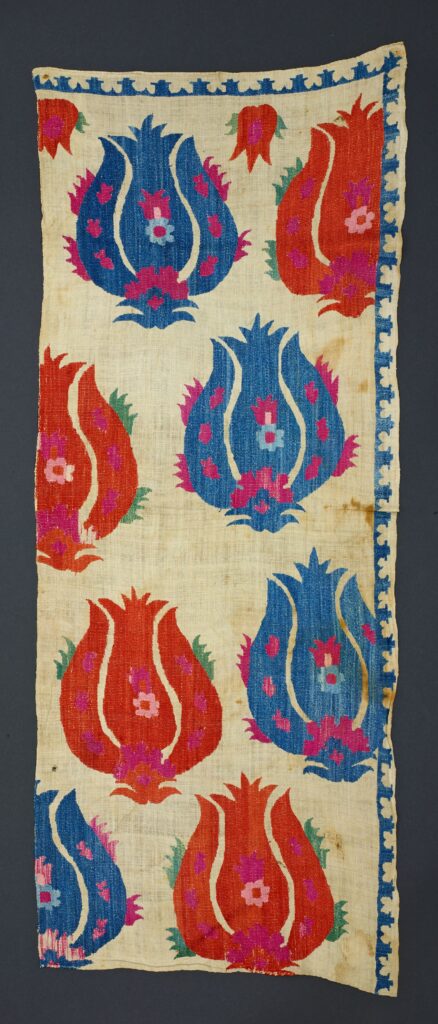

Tulip Head Embroidery

By Ayan Raja

This fragment of embroidery showcases an elegantly stylised tulip motif, a prevalent symbol in Ottoman art. The tulip, rendered in vibrant colours against a contrasting background, displays the intricate handiwork characteristic of Ottoman textiles. The petals are delicately embroidered with fine silk threads, demonstrating advanced techniques such as satin stitch and chain stitch, which were commonly used in Ottoman embroidery.

The tulip motif holds a special place in Ottoman culture, particularly during the ‘Tulip Era’ of the early 18th century, a period of peace and prosperity in the Ottoman Empire that was marked by a fascination with the flower. The tulip became a symbol of wealth and refinement, and its depiction in art and textiles signified the Empire’s connection to nature. The Ottoman tulip also became a cultural bridge between the East and the West, influencing European fashion and decoration, particularly during the 17th century when Ottoman styles were highly fashionable.

Unrecorded maker, Turkey (Ottoman), late 17th century

Linen with silk embroidery

Birmingham Museums Trust

Tulip Dish

By Lina Rashad

A distinct style of ceramic ware was innovated by skilled craftsmen in Iznik in Turkey during the Ottoman Empire. It was inherent that their practice was dedicated to beauty and excellence with the intention of pleasing Allah, or Ihsan in Islamic philosophy. This can be observed in the Islimi (biomorphic) tulip, carnation and spiral adornments on the plate. Tulips were considered the holiest flower to the Ottomans for many reasons, one of which being the same Arabic letters were used in the words tulip, laleh and Allah. Visually, the tulip also bears resemblance to the Arabic script for Allah.

The carnations symbolise renewal and power; the spirals (which are present in nature and the cosmos), convey a reverence for Allah. Overall, this stylised garden evokes Jannah (paradise).

This plate was part of William Morris’s Iznik pottery collection in Kelmscott House. It is unsurprising that Morris drew inspiration from Islamic art, as his belief that you should ‘have nothing in your houses that you do not know to be useful or believe to be beautiful’ shares a similarity to the Islamic concept of Ihsan.

The plate’s tulip motif appeared prominently throughout Ottoman culture, often stitched onto underclothes to protect against harm or misfortune. While Morris may have echoed this sentiment in personally guarding this source of his inspiration, it was unfortunately not recognised by Victorian society, in contrast to his own work. Striking similarities exist between the plate’s pattern and his 1884 design Wild Tulip, in which the same flowers feature.

Fritware, painted in polychrome, glazed

Society of Antiquaries of London (Kelmscott Manor)

Flower Garden

By Hana Mehmed

Niello is the ancient art form of metal engraving that captivated William Morris. He saw a display of pieces, taken from Damascus, at William Robinson’s showroom in 1878. Morris fell in love with the art form and began his own collection of Niello pieces from Syria and Iran. He was admired the colours and in a letter to his daughter May, wrote ‘all vermillion and gold and ultramarine very beautiful and is just like going into the Arabian Nights’, a book well loved by Victorian audiences for the ‘exotic’ landscapes and adventures depicted.

Flower Garden features flowers in hues of pale pinks and vibrant reds and shows a strong influence from the Islamic arts, through his use of sacred geometry in the symmetry, which is found in lots of artworks from the East. Its beauty can be interpreted as a collage of different art forms; the interplay between each aspect indicating the wider context in which the object existed and acting as a piece in the mosaic of Morris’s practice.

At the time, Morris’s attraction to the collection would have been seen as nothing more than a deep appreciation, however as a modern audience we can recognise Morris’s fascination is a result of colonialism and his access to these objects further exacerbates the disparity between the colonial forces and those who the pieces were stolen from. We can also now recognise that their perceived ‘allure’ augments the degree of separation, as they are reduced to objects of beauty rather than objects which harness thousands of years of culture.

Whether his attraction to Niello and the Damascus collection stems from a deep appreciation or not, the undeniable fact is that Morris built his livelihood on the designs he saw in the Islamic arts. Whilst his endeavour might have been to create objects of beauty and decoration, we cannot forget that it would have not been possible without his access to these stolen pieces of history.

Woven silk and woven silk and wool

William Morris Gallery

The Dining Room, Kelmscott House

By Tasmiya Tasmi

This photographic print, depicting the Kelmscott House dining room, was taken by Emery Walker in 1896, the year of Morris’s death. Walker was an engraver, photographer, and printer. Originally from a working-class background he shared a close friendship with Morris after they met through the Socialist movement.

This print was made using the sepia-toning process that was popular in the late 19th century for its preservation properties, warmer tones, and soft exposures. Walker’s dreamy yet sharp photograph, intended to preserve and be preserved, captures Morris’s thoughtfully arranged display showcasing iconic pieces from his Islamic World art collection, with a 17th-century Kerman rug as the central piece. Set up in the house where Morris spent his final years, this display exhibits his ultimate artistic vision and inspiration for interior design.

The stylised floral patterns in the rug follow the Islamic art tradition of Islimi, in which biomorphic, imagined depictions of nature allude to the promise of paradise, beauty, and eternity in Jannah (heaven). Additionally, Morris mirrors the rug’s symmetrical patterns using intentional pairs of artefacts, like the parallel Iranian peacock incense burners, directly demonstrating how these styles and objects influence his work. The religious connotations of the rug patterns, shrine-like symmetrical placement of precious objects, and divine ascent of the 5.2 metre long rug into the ceiling, altogether form an altar-like structure honouring craftsmanship, inspiration, and collecting, echoing Morris’s perspective of Persia as a ‘holy land’ for designers.

Emery Walker, 1896

Photograph

William Morris Gallery

Two Half-Star tiles from the Emamzadeh Yahya at Varamin

By Mara Ahmed

William Morris’s daughter, May, considered these half-star shaped tiles to be amongst ‘the greatest treasures’ of her father’s collection. A victim of over 100 years of colonial looting and theft from the ‘Orient’, the Ilkhanid period lustre tiles feature Quranic verses, (from right to left): Surah Fatiha, Ayat ul Kursi, Al Baqarah v256, and Surah Ikhlaas, as well as: Subhan Allah Walhamdulillah Wa Allahu Akbar (Glory be to Allah, Praise be to Allah, There is no God but Allah, Allah is Great).

The tiles are thought to come from the Emamzaden Yahya at Varamin, a sacred tomb located in Iran. The site itself has become a ‘curation of the void’, with the locals remembering the heritage and history behind every etching, fragment and remainder left behind.

In stark contrast, the stolen tile sits thousands of miles away, decontextualised with no reference to home, becoming void of any meaning, importance and history. Its theft unknown to Morris, the tiles are a significant reminder of the thousands of pieces of art that might never return home but can tell the story of a complicated shared heritage.

By Ayan Raja

This poem is inspired by If I Must Die by Dr Refaat Alareer, who was killed with his family by an Israeli airstrike on his home in December 2023.

Costs of Reaching the Stars

Look upon a starry night

Up above,

You will see the number of hopes and dreams

Of all those who’ve lived

The stars that have died to make more,

The energy that’s not gained or lost,

Just steadily moving.

Some of us aim to reach the skies,

Carrying the energetic ambition

Of those who believed.

Although we aren’t all able to go far,

let us reach for the stars,

the body perishes

but

Our dreams and hopes steadily move,

Moving with ones we’ve cherished.

Unrecorded maker, Iran (Ilkhanid), 13th century

Earthenware with ruby lustre decoration, mounted in an oak frame

Society of Antiquaries of London (Kelmscott Manor)

Peacock Incense Burners

By Tayyabah Tahir

These peacock incense burners are made of hollowed brass with pierced decoration and turquoise. The use of incense in many different cultures and religions has a long-held tradition — the pleasant scents are believed to uplift the soul and are used to sanctify sacred spaces. Burning incense for domestic interiors wasn’t common in Britain at the time, so metalwork like these peacocks were popularised for their aesthetics.

William Morris owned two of these peacocks and kept them as decorative pieces which he put on display in the dining room of his London home, Kelmscott House. The pierced brass depicts traditional Iranian scenes, including hunting on the wings of the Peacock and tranquil animals and mythological creatures along the base. The design also includes stylised lotus flowers among scrolling leaves. These patterns, alongside Morris’s other collected works like Iznik ceramics, share visual similarities in symmetry and floral motifs. However, Morris had a passion for all things medieval and would not have been overly enamoured to learn that these peacocks were made contemporary to his time. Nevertheless, they stayed in his home and can be seen in situ through a well-known photograph showing the interior of Morris’s house, taken by his friend Emery Walker. Through works such as this, Morris became familiar with the designs that would go on to inspire many of his own works.

c.1870, Iran

Unrecorded Maker, hollowed brass with pierced decoration and turquoise

The Society of Antiquaries of London (Kelmscott Manor)

Granada

By Saarah Ahmed & Zahra Quadri

Granada (meaning pomegranate in Spanish) velvet furnishing fabric flaunts the Andalusian and Persian textile designs that Morris greatly admired.

The repetitive pomegranate motifs that fill the design symbolise a variety of cultural interpretations. In The Holy Quran, the pomegranate is honoured as a fruit of paradise, containing healing properties. Meanwhile, its importance during the Italian Renaissance was as a symbol of purity.

The complex stems intertwining through the branches bearing fruit, showcase the artichoke as a symbol of fertility and abundance during the Victorian era. This reflects William Morris’s preference for motifs that combine natural forms instead of meretricious beauty.

Granada flourished as a centre of silk weaving during the Nasrid Period (1232–1492). The most expensive fabric was woven using luxurious silk and combined with gold thread. Morris discovered that producing silk velvet exceeded his financial expectations and ceased production.

Morris’s use of gradual undulations reflects his deep adoration for Muslim architecture, Persian flora and fauna, and Turkish influences, which are consistently found in his work and personal collection.

Designed by William Morris 1884, manufactured by Morris & Co. Silk velvet brocade with silk thread

William Morris Gallery

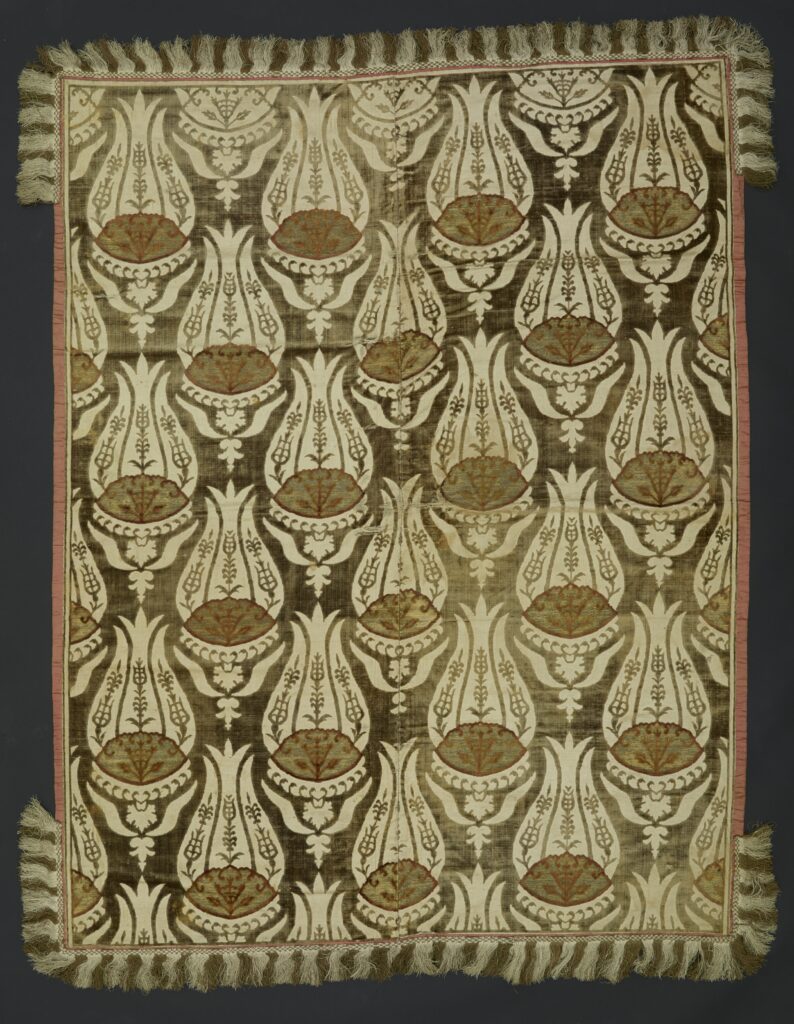

Velvet Hanging Unrecorded maker, Bursa, Turkey (Ottoman), late 16th century

By Behdad Monsef and Zara Rawat

Even beyond the grave, Morris elevated the weight and significance of Persian and Ottoman textiles, imbuing new meaning into these textures. Morris’s daughter, May, recognised the tulip as ‘all Kelmscott’, a reference to his West Oxfordshire sanctuary Kelmscott Manor. She further described the flower as one of the ‘richest blossoming of the spring garden at the Manor’.

Evidently, the tulip embodied something that transcended its visual reference to nature, and instead more broadly encompassed the nature of his character and artistry. This is only reinforced by the flower’s recurring appearance as a symbol in his work, such as Tulip and Rose (1876) and Wild Tulip (1884). Morris championed the belief that inspiration should be drawn from nature, particularly one’s immediate surroundings. As such, the tulip became a fitting emblem in his artistic and collecting endeavours.

The hanging was used to cover Morris’s coffin. Traditionally, tulips denote deep love and rebirth – two ideas that are ostensibly diametrically opposed to death. Upon closer inspection, these motifs intersect and interact harmoniously; Morris’s deep love for Persian textile design and his rebirth through the memory of his art – all symbolised by tulip embroidered fabric guarding his coffin. There is a certain poetry in the fabric graduating from the walls of Morris’s home to covering his coffin, intended to be buried deep beneath the earth – from high to low. This transition signifies a full circle, intertwining his life’s work with the natural world and embodying the cyclical essence of life, art, and nature.

It remains unclear to what extent Morris was involved in deciding that this ornate Anatolian hanging would adorn his coffin. Yet, it is abundantly clear that the essence of this particular piece resonated with and echoed his artistry and character.

Unrecorded maker, Bursa, Turkey (Ottoman), late 16th century

Voided and brocaded velvet, metal-wrapped silk thread,

cotton and silk ikat backing

Birmingham Museums Trust

Dove and Rose

By Sana Malik

William Morris perused through treasures from the Islamic world in dealers’ shops. Sprawling ornate rugs, meticulously designed manuscripts, and intricately decorated ceramics. Like the colourful florals blooming on the surface of a Persian carpet, so too did inspiration begin to bloom in the mind of Morris. His Dove and Rose pattern is an example of how these inspirations from Islamic art manifested in his designs.

Morris referred to Persia as a ‘holy land for pattern designers’, which showed his reverence for the crafts that the Persian and wider Islamic world had perfected, however these influences have often gone unacknowledged by those interested in Morris’s work.

Islamic art is frequently adorned with intricate swirling motifs. These designs consisting of spiralling symmetry, plumes of petals, and unfurling foliage, greatly influenced his work. This can be seen in the dancing vines, flowers and leaves in his Dove and Rose design. The influence that the art of the Islamic world had on his patterns is something that cannot be dismissed, as Islamic art is the mother to many of his designs, and the seed from which much of his pattern work bloomed.

Designed by William Morris, 1879, manufactured by Morris & Co.

Jacquard-woven silk and wool, with metal thread

William Morris Gallery

Agal

By Zineb Dinia

Agal

Through dunes, and stretches of sands,

In the Arabian Peninsula,

men walk under the blazing sun.

On their head, a squared cloth,

Held by a piece of rope.

Simple in its form, its processes layered with symbols,

It differentiates rural Bedouins from urban men.

To know them is to observe the strands they wear,

From wool and silk, to cotton and gold threads,

The details will reveal their stories.

As their origin is resting on their head,

Holding a square cloth, you’ve seen before.

The Keffiyeh you know today

Has travelled hundreds of lands,

Shielding from sun and wind, leading herds of sheep,

It’s faced revolutions and fought for independence.

Now it marches on the streets again,

Demanding peace in stolen lands

And an end to bombing children.

In the end, the Agal held more than a squared cloth,

It’s Keffiyeh stood for human values

beyond political views.

Unrecorded maker, Egypt, c.1896–97

Cotton, silk and metal-wrapped thread

William Morris Gallery

Resht Panel

By Sumayyah Mirza

This ‘Resht’ tent panel features embroidery and patchwork, constructed of wool and silk. This technique was popularised in the city of Rasht, in northern Iran.

This particular panel originates from the 19th century, during the Qajar Dynasty. The panel is reconstructed from pieces of an originally larger textile and stitched together with silk thread. The intricate biomorphic ornamentation features emphatic use of colour, characteristic of this period. The geometric basis of these patterns provides order to the flowing forms of the natural imagery. While the maker is unrecorded, and the journey of the piece from its source to a dealer, then May Morris is undocumented, its use and significance thereafter is known to us.

This panel, removed from its context, was exceptionally significant to May. Her reverent description of this piece is the most extensive of any in her collection, described as ‘unsurpassed’ in ‘skill and precision’. It was instrumental as a teaching aid during her career, due to its skilful technique and sublime imagery.

May mistakenly interpreted this panel as a prayer rug, highlighting its ‘durability well adapting the work to the ceaseless rubbing of devout knees’. This mistake is made obvious by the image of a face in the centre of the tent panel, suggesting secular rather than religious purpose. This oversight suggests a disregard to the cultural and religious context of this piece, owned as a status symbol rather than with genuine respect. May’s fantastical interest in this panel highlights Victorian fetishisation of Iranian art, devoid of any respect to its origins.

Unrecorded maker, Iran (Qajar), c.1800–70

Felted wool patchwork, chain stitch embroidery in silk

Birmingham Museums Trust

Slippers

By Sara Ismail

May Morris’s admiration for North African textile practices and her collecting activities underline Victorian attitudes towards Islamic material culture. The constant presence of imperialism in the collection, distribution, categorisation, and valuation of Islamic art from the late 19th century extends to contemporary museum practices.

Colonial channels facilitated acquisitions for museums, actively reflecting imperial perspectives by showcasing the European empires’ powers to collect, control, and decontextualise objects. The French occupation of Morocco, as well as Morris’s collecting efforts, definitively alter the materiality of the slippers — romanticising them as a ‘collector’s item’ and removing them from their original context. Recognising this is an attempt to address and acknowledge the imperial past of these collections.

The heelless slippers were likely purchased during a cruise along the Madeira and Moroccan coast in 1911. May travelled to North Africa twice, collecting textiles and seeking objects that were visually appealing, skilfully crafted, and suited for both decoration and function. The design is common to the Maghreb region, and features Zari embroidery, reflecting May’s keen interest in textile arts. Her management of the embroidery department at Morris & Co. and the pristine condition of the slippers, suggests they were used primarily as inspiration for her practice.

Unrecorded maker, North Africa, c.1897

Dyed leather and metal thread

William Morris Gallery

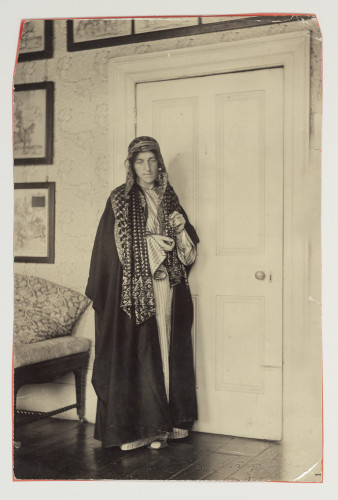

May Morris in Egyptian Clothing

By Safiyah Yacoobali

This image of William Morris’s daughter, May Morris, was taken in her London home at Hammersmith Terrace and depicts her in North African garments. The intimate setting of this image reveals Morris’s use of her father’s Apple wallpaper design, as well as what appears to be a Morris & Co. cushion cover and seat.

May wears an Egyptian Asyut scarf, which has metal embroidery to give a shimmering appearance. The scarf seems to be draped over her head — fastened in place with an Agal, which is made with animal hair and richly decorated with a metal thread, similar to the scarf. Although the origins of these garments are unknown, they may have been acquired by May during her six-month-long stay in Egypt, which took place shortly after her father’s death.

As manager of Morris & Co.’s embroidery department, May worked a lot with textiles and produced many embroidered works, including an interpretation of a North-African style cloak, similar to the one shown in this photograph. Today, in light of contemporary sentiments around cultural appropriation, viewers might feel shocked or surprised by this image. However, May’s study of Middle Eastern clothing shows a genuine appreciation of the artistry of other cultures, a trait shared by her father, who frequently drew inspiration from Islamic Art in his designs for Morris & Co. products.

Unrecorded photographer, London, c.1897

Black and white photographs

William Morris Gallery

SS Arabia Tiles

By Leyah Dean

‘To us pattern designers Persia has become holy land, for there in process of time our art was perfected’

— William Morris, 1882

De Morgan’s earthenware tile panels for the P&O cruise ship SS Arabia (1898), reflect the influence of Islamic formalised floral designs, geometry, and symmetry on his work. These tiles formed part of an extensive decorative frieze in the ship’s companionway and were evocative of an Islamic garden. However, it is unlikely the panels were from the ship, because during WWI the SS Arabia was torpedoed in the Mediterranean and sunk, with none of the decorative work surviving.

Iranian and Turkish ceramic ware, particularly Iznik tiles, greatly influenced De Morgan’s designs. His interest began with a commission to install Lord Leighton’s tile collection in the ‘Arab Hall’ at his Kensington home between 1877 and 1881.

The panels feature Islimi patterns of fruit and cypress trees, with the latter holding spiritual significance in Islamic art. For Persian mystic poet Rumi, the cypress, or Sarv, symbolised tawhid, the Oneness of God, as expressed in his writing: ‘The cypress gives hint of His majesty’. His incorporation of the ogee arch highlights how De Morgan’s work is characterised by his rigorous geometric planning, mirroring Islamic art’s emphasis on symmetry and intricate patterns. Furthermore, the leaf scroll motif at the tree base signifies the interconnectedness of life and nature, embodying the harmony of Islamic artistry.

William De Morgan, a prominent figure in the Arts and Crafts Movement, began his design career in 1863 after meeting William Morris. De Morgan transitioned from painting to design, working for Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co. He established his tile works in Chelsea in 1872, selling through Morris’s firm. Their friendship was based on creative collaboration and knowledge exchange.

William De Morgan, c.1898

Earthenware, polychrome decoration, glazed

William Morris Gallery

With many thanks to Sophie Alonso, Jo Bradford, Rowan Bain, Aliyah Hasinah (Black Curatorial), Hazem Jamjoum, Max Jefcut (Peer Gallery), Dhelia Snoussi and the front of house team at William Morris Gallery.

This project was made possible through the support of the National Heritage Lottery Fund.